21 Nov 2018

The Answers to Life Are up in the Air

It’s easy to think of our atmosphere as just an empty space above the ground, but it’s home to a wide diversity of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. These tiny life forms may hold clues to big questions, such as where and how life evolved and if it exists elsewhere in the universe. Scientists in the Aerobiology Lab at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in California’s Silicon Valley, are working to develop methods to test how and how well different types of microbes survive in the extreme conditions of the atmosphere.

What is Aerobiology?

Aerobiologists study the organisms and particles of biological origin – known together as bioaerosols – that float around in our planet’s atmosphere. Some try to understand how bioaerosols get into the atmosphere in the first place – for instance, by thunderstorms, volcanic activity, fire or dust storms – as well as how bioaerosols are lofted by prevailing wind currents. Others study the impacts bioaerosols can have, like influencing air and cloud chemistry. More questions surround how long they can stay afloat in the atmosphere and how long and in what conditions airborne microbes can survive. In recent years, aerobiology researchers have also begun to explore whether our atmosphere might hold entire ecosystems of airborne microbes and whether interactions between species in the atmosphere can allow microbes to evolve while in the air.

Aerobiology and the Search for Life

Not only is aerobiology research rewriting the book on Earth’s atmosphere, it’s also helping us understand where life might exist elsewhere in the solar system, such as on Mars. For clues, scientists in the Aerobiology Lab study the microbes that live in Earth’s upper atmosphere and what happens when we send bacteria from the ground up that high. At those altitudes, they experience temperatures, air pressure, dryness and radiation conditions similar to those found on the surface of Mars. This can help astrobiologists – the scientists who study the origin, evolution and existence of life in the universe – to conduct research here on Earth about Mars’ ability to support life.

Another link between aerobiology and astrobiology is that microbes are present in our atmosphere at a relatively low concentration, just as they might be on Mars or another planet. The sampling techniques that aerobiologists at NASA are developing to collect uncontaminated samples could help future space exploration missions searching for extraterrestrial life.

Aerobiology experiments and technologies developed at Ames and at other NASA centers are helping extend the frontiers of this research and reaching new heights in our understanding of life in the atmosphere.

Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere 1 (E-MIST 1)

This experiment, led by scientists at Ames, tested a new hardware system, procedure and instrument for studying bacteria in Earth’s stratosphere, the atmospheric layer extending from about 10 to 31 miles up. Called Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere 1, or E-MIST 1, this mission used a system that was developed at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A radiation-tolerant strain of bacteria called Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 was carried inside the E-MIST payload, which was equipped with power, a control board for self-controlled operations, customizable electronics, environmental controls and sensors. Four rotating doors made it possible to expose up to 10 bacterial samples at a time to the harsh conditions of the stratosphere.

The E-MIST payload was mounted on a large NASA scientific balloon, launched from New Mexico, and tested in flight for five hours. The E-MIST 1 mission proved that data could be collected successfully from a tightly-controlled microbiological experiment within the stratosphere. E-MIST 1 was launched in 2014.

Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere 2 (E-MIST 2)

The second Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere mission, E-MIST 2, exposed the bacterium Bacillus pumilusSAFR-032 to Mars surface-like conditions to test how well they could survive. The E-MIST 2 payload was launched from New Mexico on a NASA high-altitude balloon and spent eight hours within the stratosphere at close to 19 miles above sea level. Here, the bacteria were exposed to the stresses of extremely cold, dry air, harsh ultraviolet radiation and low air pressure.

Samples were parachuted back to Earth for analysis, and the science team found that, after the eight hours of exposure, 99.999% of the bacteria were dead, damaged, or destroyed beyond the point of being able to regrow. The undamaged few showed small variations in DNA compared to samples of the same bacteria that stayed on the ground. Fully understanding the implications of these results will require further study, but the initial discoveries from the mission have provided significant insights for aerobiology, Earth ecology and astrobiology. The E-MIST 2 mission launched in October 2015.

Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector (ABC)

The Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector, or ABC, is an instrument that was custom built at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center to capture and seal up bioaerosol samples from upstream air flowing around a moving aircraft. The ABC can collect samples while flying as high as 8.5 miles, and tackles the difficult challenge of sampling and studying microorganisms afloat at extreme altitudes.

The first mission to use the instrument, ABC-1, was led by members of the Aerobiology Lab at NASA Ames and was designed to discover the types of airborne bacteria present at different levels in the troposphere, the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere, and in the lower stratosphere, the layer above the troposphere. The research team installed the ABC on NASA’s C-20A aircraft. The research jet was then flown over regions of California and the western U.S., and the ABC collected air samples during ascent, descent and sustained cruises at altitudes up to almost 7.5 miles.

Scientists were surprised to discover a similar distribution of bacteria in the atmosphere at all altitudes studied. The mission was flown in October and November 2017, and the research was published in August 2018. The data from these flights is freely available on NASA’s space biology database, GeneLab. For more information about this data system and to view datasets for other space biology programs, visit GeneLab.

The Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector has since flown in two more missions, ABC-2 in June 2018 and ABC-3 in August 2018. The results from these missions are now being analyzed.

[Image]

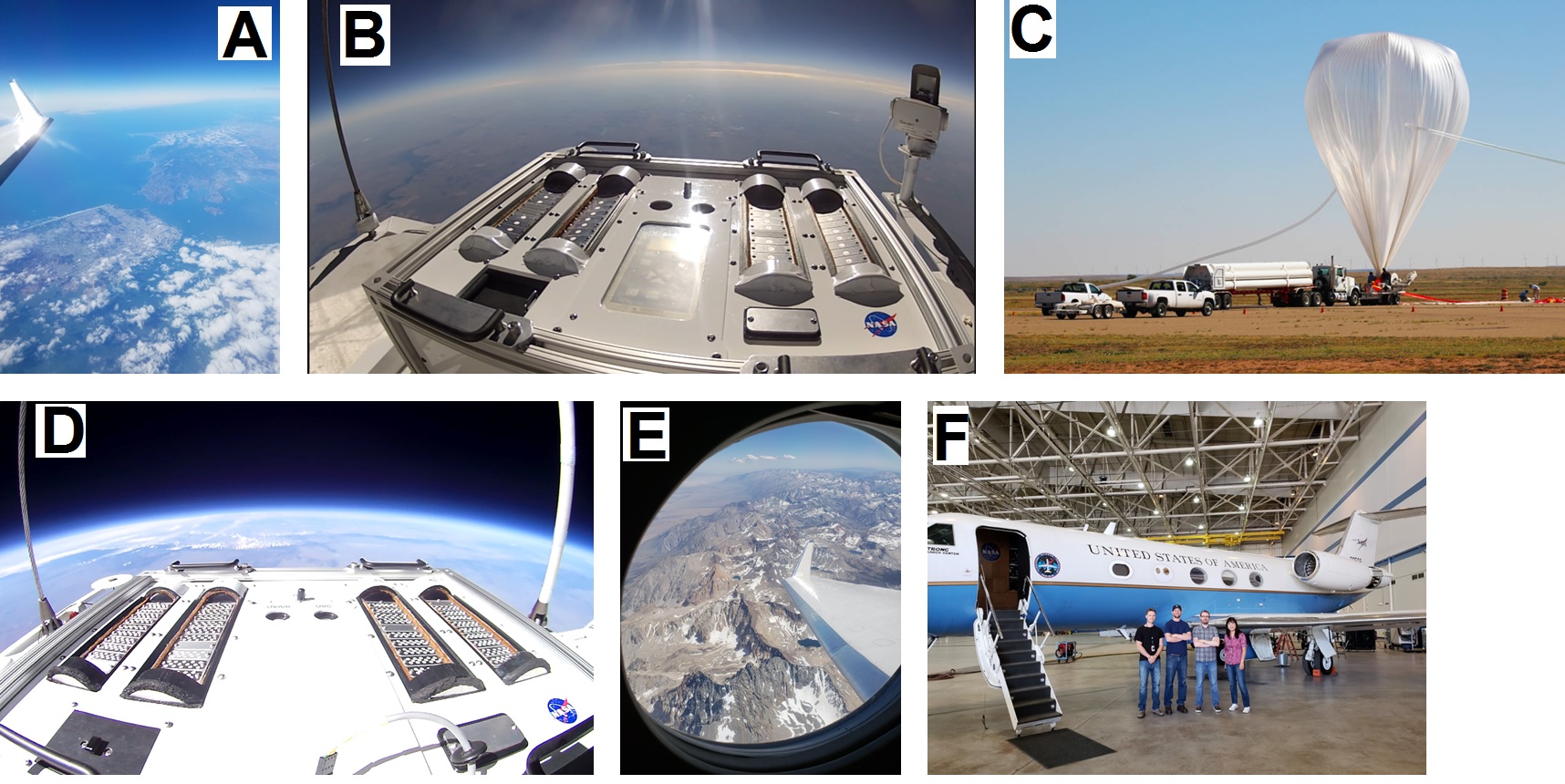

(A) An aerial view from the Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector 1 (ABC-1) science flight in the lower stratosphere over San Francisco in October 2017.

(B) The Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere 1 (E-MIST 1) payload in flight in 2014, with doors rotated open to expose bacterial samples to external conditions.

(C) A scientific balloon launch at Ft. Sumner, New Mexico, for the second flight in the Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere series (E-MIST 2), in October 2015.

(D) The E-MIST experimental hardware floating 19 miles above the Earth aboard a NASA scientific balloon. Each of the white dots contains endospores of the bacterium Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032. The hardy microbe was collected from a spacecraft assembly room, despite extensive efforts made to decontaminate such locations.

(E) An aerial view from the Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector 2 (ABC-2) science flight in the lower troposphere over the Sierra Nevada mountain range in June 2018.

(F) Science team members participating in Aircraft Bioaerosol Collector 2 (ABC-2) science flights in June 2018. Left to right: Patrick Nicoll (NASA Ames); David J. Smith (NASA Ames); James Thissen (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory); Crystal Jaing (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory).